How to Foster Collaboration with Multilingual Learners

“Now turn and talk to your partner,” says the teacher to her diverse classroom of multilingual learners after presenting them with a prompt she’d like for them to discuss. “Discuss the different types of indirect characterization that we learned about in yesterday’s class.”

And then, to her dismay, silence.

This is an all-too-common problem that many teachers encounter on a regular basis.

Although the instructional routine of “Turn and Talk” is intended to facilitate discussion and collaboration among students, it often fails to deliver the results that educators hope for.

The reason? The prompt can just as easily be answered silently and individually as together with a partner, an approach that shy, nervous students will almost certainly prefer to actually engaging in discussion in a language that is new for them.

Much of the time, MLL teachers might rely on their own energy reserves to promote discussion, or on the more socially inclined students to get the conversation going. While this approach to fostering collaboration can sometimes get the class going, it is exhausting for the teacher and will have inconsistent outcomes depending on the personalities and demographics of the class.

What is missing from the “Turn and Talk”, like many other instructional routines meant to get students talking to one another, is a reason to collaborate and clear guidance for how that collaboration is supposed to happen. Without these two key ingredients, interactions between students are likely to be stiff, stale, and unproductive in terms of the lesson’s objective.

Research has clearly shown that students benefit tremendously from participating in collaborative classrooms in which they, not the teacher, do the talking. Here are just a few of these benefits:

Exposure to an increased complexity, frequency and variety of language. When students are placed in situations where they need to be agreeing, disagreeing, negotiating, etc. they have the opportunity for a wider variety of functional use of language than in traditional exchanges in which the teacher plays a central role in all exchanges.

More equitable participation from and exposure to diverse voices and perspectives. Students, especially those at more beginning levels of English proficiency, may feel intimidated to speak in front of a whole class, but comfortable speaking with just one or two other classmates. With their ideas validated and strengthened by peers in a small group, many more students feel emboldened to then share with the larger class, thus enabling their voices to be heard.

Greater access through translanguaging (flexible use of home language). Strategically pairing students who speak little to no English with other students who are more fluent in English but also speak their home language provides a powerful scaffold and entry point to classroom activities. For many collaborative activities (brainstorming, negotiating, prioritizing, etc.), students can and should be encouraged to use whatever language or language(s) they wish even if they eventually have to produce something in English to share with the larger class or to communicate their understanding to the teacher.

Increased student engagement. Our general guideline when coaching teachers is that if they are speaking for longer than three-minute stretches at a time, they will most likely lose the majority of MLLs at beginning English proficiency levels in their class. Studies have shown that greater engagement in a collaborative classroom also leads to greater retention of material.

Improved interpersonal skills. By explicitly teaching interpersonal skills to students and then providing them countless opportunities to practice applying them, teachers better prepare their students for the 21st century workforce.

So if collaborative support is lacking in classrooms, students stand to lose quite a bit from the quality of their educational experiences. All teachers of MLLS should strive to incorporate these measures into their lessons. The problem is that most teachers do not know how to do so.

One of the main issues that complicates this is that many teachers might confuse the concept of “group work” for true collaboration. In group work, the teacher may simply assign students into groups to work on the problem or project at hand, without much guidance in terms of who takes on what role, or how to communicate ideas to one another. But this is different from true collaboration, in which the teacher has strategically structured the activity such that students must rely on one another in order to complete the activity.

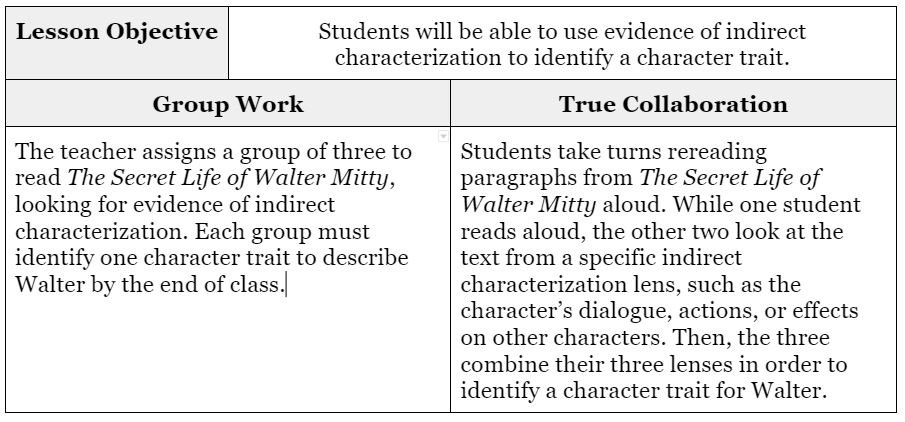

To get a better sense of the difference between group work and true collaboration, let's imagine an ELA class in which the teacher wants students to look for evidence of indirect characterization in order to identify a character trait for the protagonist. Take a look at how group work might be organized versus true collaboration:

As you can see, collaboration in the group work version of this assignment is more of a suggestion, but students might be unclear as to what role they are to play. Perhaps there might be a Type A student who takes the initiative to do so, but that is certainly not guaranteed. By contrast, in true collaboration, each student has a specific role through which to view the text, and all roles are required in coming to a consensus about the best answer to the prompt.

One of the main differences between group work and true collaboration is the use of micro-structuring, the process of providing more structure to an activity. The structure can be added in several ways, listed below:

Grouping students according to the number of meaningful roles within a task, as the example on indirect characterization demonstrates.

Using an activity structure with protocol, such as Think, Pair, Share.

Promoting structure independence from the teacher through the use of a graphic organizer that is designed to facilitate the activity from start to finish.

While this blog has provided you with some ideas for the initial steps in implementing truly collaborative activities in your classroom, the real “Square One” for embarking on this journey begins in your own mind.

Transforming more teacher-centered activities within a lesson plan to those that are more student-centered requires more than just a rethinking of the activities themselves; it requires a shift in mindset about the nature of learning.

Part of this mindset is the belief that students will benefit more from learning from each other instead of just from you, since they will be required to actively construct knowledge through brainstorming, debating, and negotiating with one another instead of passively taking notes on the new knowledge that you have shared with them.

Another aspect of this mindset involves ceding control (this can be hard for teachers!) in a different way: the need to know exactly what all students are talking about at all times.

Yes, it is possible that students at times will veer off task and you won’t always know it the second it happens, especially if they are speaking in their home language instead of English.

We would posit that you also don’t know when their minds wander off task as they lose interest when teacher talk goes on too long.

A collaborative classroom is of course louder than an orderly teacher-centered one, so tolerance of noise is important. This goes back to having the mindset that collaboration is important for productive learning so more noise is an easy trade-off to make.

The truth is that a lively, collaborative classroom is one in which learning is happening at a much faster rate with more efficacy in terms of student outcomes.

How to Foster True Collaboration in YOUR Classroom

Are you ready to learn more about the design of true collaboration, such that your MLLs are provided with everything they need to be successful? Then check out our upcoming event on October 27th, Fostering Collaboration for Multilingual Learners.

In this workshop, you will learn more about the differences between group work and true collaboration, understand key components of micro-structuring activities, and then identify opportunities to add true collaboration into lesson plans.

Finally, the facilitator will share resources with you that allow the implementation of new learning into your classroom TODAY., resources that you will be able to use again and again throughout your teaching career.